Maestrino Mozart: youthful operas

Every time I think in my mind of writing an opera, I feel as if my body were afire, and tremble from head to foot.

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart,

Letter of July 31, 1778

These days, everyone knows of Mozart’s astonishingly precocious genius. As a child, he wrote fine sonatas and symphonies and, spurred on by his father, Leopold, who was eager to make his son known throughout Europe and assure his future, was already irresistibly attracted to the idea of writing operas.

At that time, in Austria and those parts of Germany that had remained Catholic, Italy dominated all the arts. For decades, composer and musicians had been crossing the Alps from Italy, effortlessly establishing their aesthetic standards in music, particularly in the genre of opera. According to Edward J. Dent, German composers “were all the time subconsciously expressing themselves in a musical language that was essentially Italian”. Yet, the period of supremacy of the great Italian school of music was, after 150 years, coming to an end. The German masters, without being fully aware of this, were preparing to take over…

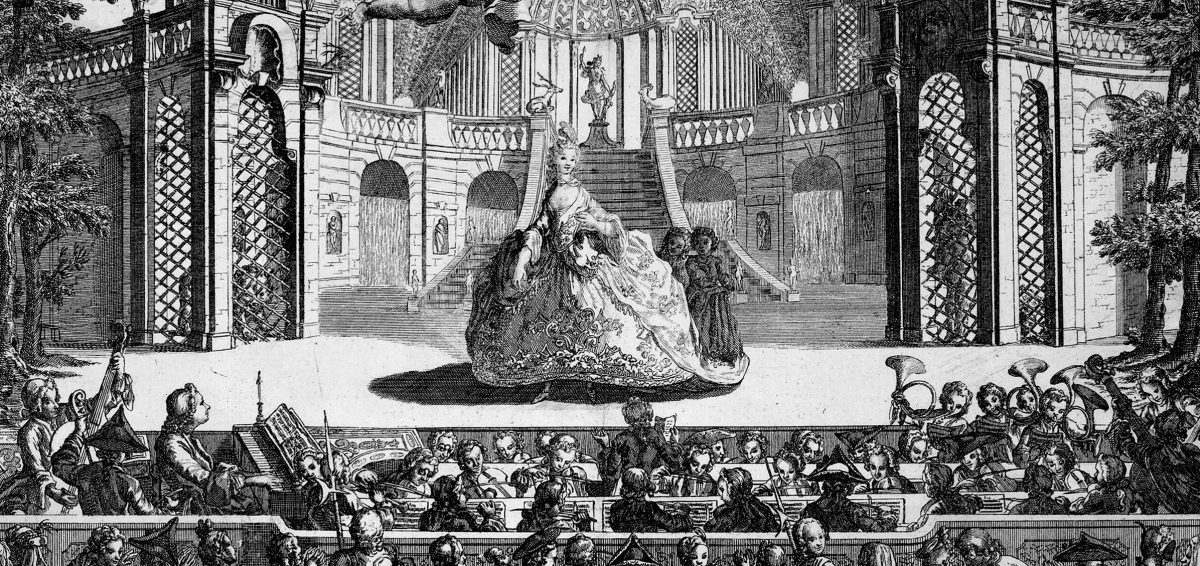

Mozart à Milan en 1770

Two types of opera were performed at the time. Opera seria, serious opera, the nobler form, involved complex plots drawn from mythology or ancient history. They concerned conflicts of love, duty, fidelity, and treason, and the action was advanced by recitatives, interspersed with arias expressing the characters’ emotions and thoughts. Outside of Italy, opera seria was a genre reserved for courts, for aristocrats and ruling families. On the other hand there was opera buffa, comic opera, lively and ‘natural’,with stock characters—peasants, villagers, servants, and bourgeois—enacting stories of criss-crossed love, slapstick schemes, fakery, and implausible misunderstandings. Closely related to opera buffa was the German-language singspiel, a genre derived from the French opéra-comique and in which dialogue sometimes replaced recitative.

Starting around 1760, there was a move to enhance the dramatic structure in opera seria. Rather than a linear sequence of arias and recitatives, more integrated scenes were being devised, with the recitatives accompanied by the entire orchestra—essentially monologues in which characters expressed their inner torments. Over time, arias, which were in da capo form, with a repeated first section, had been growing much longer. This gave star singers—prime donne and castrati—abundant freedom to show off their vocal chops, but slowed down the development of the drama. In response, more concise forms such as the cavatina were developed; vocal ensembles began to sing to wrap up each act; since plots needed more variety, the conventional poetry and naturalist metaphors of the model libretto established by Metastasio was abandoned; and the orchestra, now larger, not only expressed emotion but also took part in the dramatic action.

Young Mozart participated in all these developments. From a very young age he was eager to translate passions, from the noblest to the slightest, into music; and he was fascinated by the stage. Already, in 1764, Leopold wrote that “now he always has an opera in his head.” Brigitte Massin sees in this the effect of the tours which his father made the boy Wolfgang undertake. “He was, and remained throughout his life, someone with a remarkable gift for dramaturgy. […] Does not travel stimulate the imagination? This young star entertainer, wandering the western world, was shaped by the theater of his European journeys […] Opera would itself be a game of theater and song, a game in which words encounter music.”

As soon as the opportunity arose, Mozart began composing works for the stage. He tried his hand at opera buffa and dramma giocoso; singspiel; opera seria, a genre that appealed to him all his life; and its derivatives such as the serenata and the azione teatrale, these being large-scale staged cantatas featuring sometime allegorical characters but lacking a plot. Brigitte Massin writes: “In its long evolutionary path, opera occupied the composer almost his whole life: from his very first expression of interest in the form, in London, and his childhood years to The Magic Flute and the end of his life.”

Une prima donna sur la scène du Teatro Regio Ducale de Milan vers 1750

By absorbing the works for stage of his Italian and Italianized predecessors, as well as the art of their singers, Mozart developed a profound understanding of bel canto singing. He worked in close collaboration with singers, adapting his music to the voices available to him. But, even while still quite young, he refused to be swayed by the whims of stars, to countenance their desire to improvise; rather, he fully notated the vocal ornaments which he deemed appropriate—some of which are quite difficult to execute. And from an early age he wrapped his arias in sumptuous orchestrations. By giving the winds increasingly important and often fully exposed roles, German composers had only recently surpassed Italians as orchestrators. Mozart was no exception In the words of Edward J. Dent, he “had habituated his mind to thinking in terms of the symphony, and conceived voices and instruments all as component parts of an organic whole.”

His earliest lyric compositions were concert arias. His first such work, on a text by Metastasio, the accompanied recitative O temerario Arbace and the aria Per quel paterno amplesso, K. 79, may have been written for an academy in London in 1766. One year later he wrote Die Schuldigkeit des ersten Gebots (The Obligation of the First and Foremost Commandment), K. 35, a sacred singspiel in which allegorical figures discuss the bases of faith. The Archbishop of Salzburg, Sigismond von Schrattenbach, had commissioned three composers to write a three-act sacred drama. Of this work, only the first act, written by nine-year-old Mozart, survives.

Bastien und Bastienne, K. 50, a one-act singspiel, a simplified adaptation of Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s Le Devin du village, was probably performed in 1768 in the gardens of Dr. Anton Mesmer in Vienna. Fearing that she is no longer loved by Bastien, Bastienne asks the village devin (soothsayer) for help in rewinning her lover. The Intrada, an introduction in rustic style, leads into the first aria, sung by the troubled Bastienne.

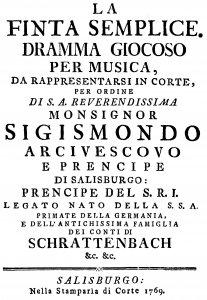

La finta semplice

In that same year, Leopold planned to have his son compose an opera buffa for the celebrations surrounding the marriage of an imperial princess in Vienna; unfortunately, she died of smallpox before the wedding! The Mozarts tried to have the opera performed nonetheless but, though they enjoyed the emperor’s protection, various intrigues foiled their efforts. La Finta semplice, K. 51, a dramma giocoso on a libretto based on a work by Goldoni, was finally first performed in Salzburg, at the palace of the Prince-Archbishop, in 1769. Mozart reworked his Symphony No. 7 in D major, K. 45 to produce the opera’s overture, dropping the minuet and slightly changing the orchestration.

Mozart wrote his first opera seria while making a major tour of Italy in 1770. Mitridate, re di Ponto, K. 87, with libretto based on a tragedy by Racine, was first performed at the Teatro Regio Ducale in Milan, with a large orchestra, on Dec. 26, 1770. The action, which concerns the love for noble Aspasia felt by both Mithridate and by his two sons, takes place against the background of a war against the Romans, with plots and betrayals. The work was Mozart’s first big success—it was performed about 20 times—and the 14-year-old composer was saluted by cries of Viva il maestrino! (Long live the little master!).

Il Sogno di Scipione, K. 126, a serenata drammatica (dramatic serenade) in one act, was composed in 1772 to honor Archbishop Schrattenbach on the 50th anniversary of his ordination. He died before it could be performed, however, so it was rededicated to, and premiered for, his successor, Count Hieronymus von Colloredo. The libretto, by Metastastio, is based on Cicero. It tells the story of General Scipio Africanus the Younger, who dreams that Constancy and Fortune are arguing over the honor of protecting him. After also meeting his illustrious ancestors, Scipio, of course, chooses Constancy…

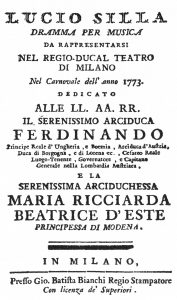

Lucio Silla

After the success of Mitridate, the Teatro Regio Ducale in Milan commissioned a second opera seria from Mozart. The result, Lucio Silla, K. 135, was premiered in December 1772. Roman dictator Lucio Silla lusts after Giunia, who loves another. He plots to kill her, and others plot to kill him. After multiple adventures, Silla pardons everyone and renounces his dictatorship. This work also was performed some 20 times.

Should we judge these youthful works by Mozart against the standard set by the great operas of his Viennese maturity? They do not measure up, of course. In fact, nothing written in that period reaches the high level of psychological truth of these great operas’ characters, the fruit of the composer’s collaboration with an exceptional librettist such as Da Ponte, his absolute mastery of the art of writing both for voices and for instruments, and his staggering ease at surmounting all difficulties. Yet many aspects of his youthful operas, though written before he became the genius we know, still exude his characteristic seductive charm. Marie-Christine Vila writes: “from his first compositions onward, all Mozart’s music is imbued with his stylistic signature; thus we are surprised, at the turn of an air, at the phrase of a recitative, at an orchestral intervention, to hear melody, accents, or a timbre worthy of his most beautiful works.” Let us not deny ourselves such pleasures!

© François Filiatrault, 2021

Translated by Sean McCutcheon

The concert Maestrino Mozart with soprano Marie-Eve Munger will be presented on October 29th, à 7:30 p.m at the Église Saint-Laurent.